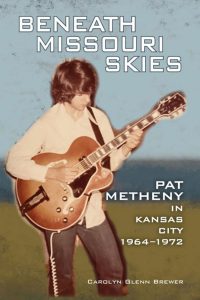

Beneath Missouri Skies: Pat Metheny in Kansas City 1964-1972

Downbeat Scholarship

In the fall of 1968 Pat saw a notice in Downbeat announcing a scholarship competition for the National Stage Band Camp. “I got Kevin [Clements] and Dru [Rachaner] and another good friend of Mike’s, Richard Jorgensen, who played flute,” Pat recalls. “Dru had a fancy reel-to-reel recorder and we went to my dad’s garage and set up. We played ‘The Big Hurt,’ one of Wes’s [Montgomery] tunes.” He didn’t hear anything back so assumed nothing had come of his application. “Then, in about the first week of the following June, the new Downbeat came in the mail, and I was flipping through it, and there was the article that announced the winners. I had won the full scholarship! That was how I found out.” Because they hadn’t received any notice from Downbeat, Pat remembers that his mom called the magazine’s Chicago office for confirmation, and got it. “That was a really exciting day.”

Kevin and Dave Glenn were anxious to go, too, so the Methenys drove them all to the camp. Once there the boys immediately found a room to warm up in. Dan Haerle, who was there to teach jazz piano and coach a big band rhythm section, heard them and tells what happened next. “The first day at Millikin I walked into a room and saw Pat, Dave Glenn, and Kevin Clements playing. I sat down and listened to them play, and when they finished, they asked if I could work with them

during the week.” Dan goes on to say that there was no scheduled time for combos; all the focus was on big band. “It was strictly an extracurricular activity.” Dan, who was at the beginning of his long and honored career as a jazz educator, recognized that something special was going on in that room. “Pat was impressive in his technique and his ability to play rapid patterns on the guitar. Added to that, these boys understood that the only way to learn to improvise is to play in a small group, not a big band.” So although each day that week was packed with big band activity, Dan agreed to work extra with the boys. “I was happy to do so.”

Pat was attracted to this camp largely because of Attila Zoller’s presence. Having the opportunity to study individually with him proved to be a life-changing experience for Pat. He explains, “I really did learn a lot from Attila. It was the first time I had been able to ask someone who really knew what they were doing on the instrument some basic stuff about how to play. I had sort of just been winging it up to that point.” The older guitarist saw potential in Pat. “My playing was pretty raw at that stage. Attila said I should come to New York and hear the real players and what the level was. He invited me to come any time I wanted, and he would take me around.”

Pianist and composer Marian McPartland was also there. In a 2005 Piano Jazz interview, she and Pat reminisced about Pat’s early writing. At the camp he debuted a new, original tune called “Charged.” Marian remarked that it was an unusual title, so Pat told the story. He had noticed that big-time arrangers had rubber stamped names at the top of their charts. “My dad owned a business, and the only rubber stamp he had said, ‘Charged,’ so that’s what I named the tune.”

Landmark Mini-Festival concert February 1972 Gary Sivils and Four

. . . Most tunes would have been anti-climatic to this. Gary and Four had pulled the audience up to a fevered level of musical emotion. But what the group had in store for the closing piece would bring everyone to a second climax. In retrospect, each thinks another came up with the idea, but they all agree that the electronic psychedelic tease they mixed up for a prolonged intro was, in Brooks’s [Wright] words, “meant to be free and chaotic sounding like what we heard in places on some of Freddie Hubbard’s CTI records.” Gary remembers that Pat wanted to do this arrangement of “Eleanor Rigby,” inspired by Wes Montgomery’s version. “It was all so new and just kind of fun,” says Paul. “I was an old bebop player, but I thought, ‘Yeah, let’s go crazy on this.’ We enjoyed playing a little outside and shaking up the audience.”

Gary remembers the form. We played it straight for one chorus with a rock beat and then went into this 4/4 double shuffle time and just played. Everyone took solos—we did as many choruses as we wanted and then handed it off to someone else— and it got crazy. At the end we decided to do what we called the freak out ending, where you do what you want to do, no tempo or anything. Paul had his wah-wah pedal and phase shifter going, and Pat was playing feedback on the guitar. I turned my echoplex to a figure-eight loop, so I had seven other trumpets going.

Paul remembers wondering before he started who in the crowd would like it and who wouldn’t. He didn’t reflect for long. “Should we do it anyway? Hell yes.” David [Belove] says the organizers of the mini-festival were well aware of the quality Gary and Four would bring to the concert and that the band wouldn’t be bringing a standard bebop set list. “Echoplex trumpet doesn’t work with bebop,” David states. “I don’t remember having a rehearsal for this gig,” says Brooks. “These were tunes we did at the Ramada. We were just keeping up with what was happening at the time. I don’t think we played differently that day other than with a lot more enthusiasm.”

But Gary remembers that extra level of enthusiasm defined a moment. “That band absolutely exploded. I never heard Brooks play better than that afternoon. He just uncorked it. I get excited just thinking about it.” He also felt he watched Pat blossom that day. “He played his ass clean off,” Gary says. “While Pat played his solo on ‘Eleanor Rigby,’ I was standing on the other side of the stage with a clear visual shot. We were cranking everything up and when he got into the free part of his solo, he started shaking his head back and forth and playing up and down the neck. He was completely inside the music. I thought at that moment, ‘God Almighty, I’ve got a rock star on my hands.’” By Gary’s account, their playing of “Eleanor Rigby” brought the people to their feet, and some even to the tabletops so they could get a better look. “They wouldn’t quit clapping. The audience had never been subjected to this crazy freak out stuff in their lives. We couldn’t get off the stage.”

Pat was scheduled to play with Warren Durrett’s Big Band next. He changed into the polyester maroon band jacket Warren’s musicians wore (band members adopted the moto “swing and sweat with Warren Durrett”), but the applause kept up. Arch Martin, who played trombone in Warren’s band that day, passed Gary on his way to the stage. “Arch put his hand on my shoulder and yelled over the noise, ‘We might as well go home. This damn concert is over with.’”

First time Herbie Hancock heard Pat play

In August, just weeks before Pat’s departure for Miami, Pat, David [Belove], and Brooks [Wright] serendipitously found themselves playing for Herbie Hancock. They already knew Herbie’s much anticipated, five-night gig at the Landmark would be a summer highlight. So much of what they were trying to do individually and collectively as a trio was inspired by Herbie and the musicians he had with him.

Pat told Bob Gluck, author of You’ll Know When You Get There, a book about this band, that “hearing that band live was simply the greatest thing I had ever seen or heard up to that point. I would say that the gigs that week remain in the top three musical memories of my life. Whenever I think that I might be getting to something good, I always reference it to what I heard on those nights.”

Monte Muza was there too. . . Always Pat’s most enthusiastic promoter, Monte told Herbie about Pat. Then he told Pat he’d been hanging out with Herbie Hancock. “I just brought it up and Pat asked if I could bring Herbie to the trio’s daily session. I don’t think that Pat thought that I’d actually do it.” But he did. . . . They decided on a day and time and that they’d meet at Brooks’s house. . . Then they got busy figuring out what to play [and] decided to do the pieces they had been working on all summer, including a couple of Pat’s originals.

. . . [When Herbie and Monte arrived] Pat, David, and Brooks, exchanged a few pleasantries with Herbie, offered their hero the most comfortable chair, and started off with “Struwwelpeter.” “Herbie was right there, in full Mwandishi garb, checking us out,” says Pat. “I was sitting, and I remember looking down and my knees were shaking.” Although it was clear the Pat was “the most nervous I’ve been in my entire life,” from the start Herbie showed interest in the young guitarist Monte had brought him to hear. “Brooks and I were pretty much the support team for Pat,” says David. They played a few tunes and relaxed a bit, although Pat recalls that Herbie said something to him about his time. “He said, ‘You’re kind of rushing,’ and I was shaking so hard I’m sure I was.”

When they were finished playing, they asked Herbie for advice. “Just keep doing what you’re doing,” Brooks remembers him saying. “We’re all musicians, honoring the music. We’re no different in that.” Herbie’s example, set in that statement, already experienced in the attitudes of Clark Terry, Attila Zoller, Wes Montgomery, and Cannonball Adderley, left a lasting impression on Pat that would forever remind him of the constant truth: it’s all about the music. When he left, Herbie gave Pat his card. “I still have it.”

Changing The Tune, The Kansas City Women’s Jazz Festival

Visit KC Women’s Jazz Festival Memories Facebook Page for teasers and photos

Now’s the Time

The morning after the Wichita Festival, Dianne called Marian McPartland. The two had met when Dianne interviewed Marian over the phone for her Women in Jazz radio show.

“I wanted to get Marian’s take on the idea of creating a women’s jazz festival,” Dianne recalls. “It still seemed like a good idea to me in the morning, but I knew Marian would give me her honest opinion about the feasibility of putting something together.”

Dianne was well aware that the jazz scene was in flux and of how fickle jazz fans could be. Just the year before, the thirteen-year run of the Kansas City Jazz Incorporated Festival had ended, largely due to changing trends and a drop in attendance and revenue. Several very talented young players had recently left Kansas City—Bobby Watson, Rob Whitsitt, Danny Embrey, Rod Fleeman, Pat Metheny—following the tradition set by Charlie Parker, Count Basie, and countless others. It wasn’t just the idea of women musicians that Dianne wanted to ask Marian about. She wanted the perspective of someone from out of town. She wanted to just put it out there: How successful could another big festival in Kansas City be?

That phone call gave the idea its first breath. It was kismet.

“Oh my God, what a wonderful idea!” Dianne remembers Marian’s instant enthusiasm for the idea. “I wish I’d thought of it myself. I’ll do anything to help.”

Well into her fourth decade as an internationally known jazz pianist, Marian had the excellent reputation, the contacts, and the gregarious personality to make that offer invaluable. The first thing she did was put Carol and Dianne in touch with Leonard Feather, a long-time champion of women jazz musicians. Although years before Feather had written in an article for Down Beat that as a jazz musician McPartland had three strikes against her—namely she was white, British, and femaleii—their mutual respect for one another and common support of egalitarian jazz had developed into a trusted friendship. Besides, Marian had proved Leonard wrong.

Long known as a jazz critic and record producer, Feather had put the spotlight on scores of female musicians with his Down Beat column, “Girls in Jazz.” He had a sixth sense about new talent and, as jazz critic for the Los Angeles Times and the British magazine Melody Maker, plenty of opportunity to exercise that skill.

“Marian said she’d take care of finding people on the east coast,” Dianne says, “and Leonard could take the west coast.” Carol adds, “Dianne and I already had people in mind, but with this kind of input right from the beginning, we were ecstatic.”

Sweethearts of Rhythm

“This is unbelievable. I never dreamed we’d be all together again.”1 Singer Evelyn McGee took the stage at the Meeting Place in Crown Center for the tribute to the International Sweethearts of Rhythm. Although not strictly an original Sweetheart, Evelyn had joined the band while it was still affiliated with Piney Woods School and thought of this event as a school reunion. She and her husband, former arranger for the band Jesse Stone, had come at their own expense to be a part of the afternoon. As Evelyn launched into “Unforgettable” at the Sunday afternoon tribute, she couldn’t help but make it more personal. “Carol Comer, you’re unforgettable,” she sang out. “Dianne Gregg, you’re unforgettable. All my Sweetheart sisters, you’re unforgettable.”1 Marian McPartland, who had played at another venue the night before, accompanied Evelyn. Initial contact with the Sweethearts had come through Marian, and she told the crowd she wouldn’t have missed this. Her awe of the older women was apparent. To the crowd’s delight, drummer Pauline Braddy, who hadn’t played in twelve years, and trumpeter Nancy Brown Pratt, who borrowed a trumpet from a Maiden Voyage member, joined Evelyn and Marian mid-tune and finished with them on “I Cried for You.”

Carol and Dianne had made it clear in a letter to each Sweetheart earlier in the year that there would be no pressure to perform, but that all would welcome a spontaneous jam. “We are bringing you in to honor you and not put you on display. If you want to perform, we would LOVE it—but we don’t want any of you to think that performing is part of the deal. . . . We only want you to have a super time.”

A big part of that super time was to hear Maiden Voyage and to see first hand what an all-girl band, circa 1980, could do. Ann Patterson told the audience that none of what they did would have been possible without the trail the Sweethearts blazed forty years before. From the Friday night concert, they reprised their original “Pretty Good for a Girl” with the bitterly tongue-in-cheek lyrics, “You’ll learn to cook and to sew, once more you’ll like it, I know,”1 sung by the entire band. For the rest of the afternoon, the band stuck to stock arrangements rather than playing covers of Sweetheart tunes. The afternoon juxtaposed then and now.

Wearing nametags decorated with large red hearts, each Sweetheart was called to the stage to receive a sweetheart rose from emcee Leonard Feather. “This is an emotional afternoon,”1 Leonard, visibly touched, told the audience. Besides recording the group in the late forties, he had done publicity for the band. In a casual manner, he asked each Sweetheart questions about their time with the band. Willie Mae Wong, baritone saxophone, told about her time as treasurer and the meager eight dollars weekly stipend each girl received. Helen Saine recalled that, although she “turned pro” along with the other girls, when the band set up housekeeping in Virginia, the juvenile authorities sent her back to the Piney Woods School until she turned sixteen. Right after her birthday, she was back with the band. Helen Jones recounted for the audience the rehearsal schedule they stuck to on and off the road and how their various musical directors drilled them on basics. For Evelyn McGee, sitting in with the band one night when she was a teenager convinced her she wanted to go on the road. Remarkably, her mother gave her permission, and Evelyn left with the band that night. “I didn’t even have a real suitcase. I carried my things in a cardboard satchel.”

Undoubtedly the most sobering of the stories belonged to alto saxophonist Roz Cron. Although she tried to disguise herself during gigs to keep the southern authorities at bay, they caught up with her in El Paso. As she walked to an after-gig restaurant escorted by an African-American GI who had just attended the Sweethearts’ performance, police circled, then stopped the pair. After hassling the serviceman and sending him on his way, they focused on Roz. “I wasn’t supposed to fraternize with blacks. I tried my usual story of being mulatto, but the policeman looked through my wallet and found the picture of my very white Jewish parents standing in front of an obvious New England house, white picket fence and all. I spent the night in jail.”

Not even memories of the Jim Crow south could squelch the delight of renewed contact after so many years. “I can’t believe this is happening,” Anna Mae Winburn told the crowd. “I feel like I’m in the Twilight Zone.”

Caught In The Path

Would it hit? Would the tornado bear down and throw them into chaos? Or, at the last second, would it veer off in another direction, or hoist itself back into the clouds? There was little time to prepare, less time to think, but everyone tasted fear. There was the unmistakable shudder of disbelief. Selfishly, ravenously, it claimed everything in its way, demanding residency.

Time ran out, sucked into the vortex along with everything else. As I slept through those last seconds of peace, a community held its breath.

At first there was silence, breathless, terror-filled silence, as though the tornado had claimed all sound for itself. Then, as people let go of each other and opened their eyes, moans and cries punctured the striped air. Some made it out of houses and basements in time to see the twister roar off into the northwest, as it wrote its signature through another few miles of farmland and woods.

No church bells rang at the Presbyterian Church that Sunday morning May 26. The congregation came anyway. They came to be together where they felt safe, where many of them sought shelter that past Monday night. It was too much to comprehend that only last Sunday the main topic of conversation had been the first anniversary of the church’s dedication: dedicated on May 20, 1956, destroyed May 20, 1957.

But nature wasn’t quite ready to let go. The storms were frequent and fierce that summer, and everyone in the area felt more vulnerable than ever. Nightmares were very close to the surface. As residents looked out at turbulent skies, at lots still uncleared and overgrown with tenacious clumps of grass, at old friends constructing new lives, neighborhood never meant so much.

Survivors

“The tornado was wide and short and the ground shook. Coming across the Kansas state line straight at us it was hitting nothing but timber. It rolled me and I saw the current coming around the smaller house as it exploded. Walls just bowed and then disappeared where a few minutes before people had stood… A Studebaker hit me. It was scooting on its back bumper and I got hooked up in it and then it took off bouncing on the ground. That’s what broke my leg… You’re sitting there and then in an instant everything’s gone. You cannot explain the power.”

Stanley Jeppeson, Martin City Resident

“I grabbed hold of our three-year-old Denise’s arm. It just seemed like for a second or so time stood still and I looked at her face. Time was frozen. She was just petrified. I never will forget the look on her face. I had hold of her arm and the tornado sucked her up. I pulled her down and it sucked her up again. It sucked her up a third time and I tried to pull, but God’s angel just opened up my hand and I felt a voice saying, ‘Let go, I’ve got her.’ That’s the feeling I had. It was like a spirit telling me.”

Treva Woodling, Ruskin Heights Resident

Caught Ever After

First the smell. Sour, earthy, the inside smell of things never meant to be opened. The black smell of the feverish nightmare behind my eyes.

And then with a jolt, as the window screen falls on top of me, I’m awake. My face is hot and my eyes burn and the nightmare is inside my room.

Through the murky, dust-filtered light I can see my toys frantically dancing like a chorus of deranged marionettes, or like the skeletons in the Halloween cartoon they show on the Mickey Mouse Club. Some are flying out the window with the curtains and some of my furniture. Will I be next? The bookshelf headboard behind my bed is jumping up and down too, making it seem like it’s raining books. But I’m seven, and I know that cartoons are make-believe. At least that’s what all the grownups say.

As we bury our faces into the pillow, I hug my doll, Sweet Sue, closer to me and tell her not to cry. Where are Mommy and Daddy? Where’s David? He’s smaller than me and could easily fly out his bedroom window.

It must be a giant, a very large, angry, monster giant who’s also very selfish. I can’t make out “Fe, fi, fo, fum” through the awful roar, but he has to be at least as big as the giant in “Jack and the Beanstalk.” He’s taking all the air in the room too and it’s hard to breath. Mommy and Daddy will never hear me.

Why would a giant monster want to come into my room and take my toys? I brushed my teeth and said my prayers. I even ate all my spaghetti at dinner, cleaned my plate just like Mommy asked me to. Just a little while ago Daddy sat at the edge of my bed and read Sweet Sue and me bedtime stories and tucked us in. David couldn’t be in here because tonsillitis is catchy, and I had to go to bed early so I’d get well. Can monsters catch tonsillitis?

The monster is throwing things at me, and it hurts. Bits of the walls and ceiling are falling all over the room, but some are coming right at me, hitting me everywhere. I try to cover my heard, but my hands are too small. And I can’t pull up the covers because they are stuck underneath the window screen, which is also being pelted with stuff, and that pushes me further into the bed. Why doesn’t Daddy come in here and get me? Why isn’t Mommy holding me? Pretty soon I’m going to be buried in things from my room, and they won’t be able to find me.

I think about trying to push the screen off of me and making a run for it, but that’s too scary because my door is rattling and banging so hard that I think there must be another monster on the other side trying to get in. Where is everybody? Maybe I’m all alone in the house, alone with the monster. Is it because I’m sick?

When I try to turn toward the wall and push Sweet Sue down under me more so the monsters won’t see her, I notice there’s a chip out of her forehead. Then I see blood on my fingers. I touch my forehead where it hurts, where my hands were trying to cover my face, and I can feel I have a chip out of my forehead too. I pull my hand away and more blood runs down my fingers. Now I’ll get in trouble for getting blood all over the sheets, and still the monsters won’t be quiet and let me get up out of bed. What am I going to do? I promise I’ll never scratch David again or whine when Mommy brushes my hair. I don’t want to be here in this room alone. Please God, let the monster go away and leave my house so I don’t have to be alone. Please make it like it used to be. Please make it stop!

And then it’s gone. Something is pounding inside my head, like my heart is trying to come out through the chip in my forehead, and my throat hurts more than ever. My ears are stuffed with silence. My mouth feels like it’s full of sand. But there are no monsters. I think there are no monsters. I hope they aren’t playing a trick on me. I hope they haven’t stopped to take bigger breaths so they can blow down the rest of the house. I have to get out. I kick and wiggle until I push the window screen off of me, but there’s glass everywhere and I can’t see my shoes in the dark. I crawl to the end of the bed and, careful not to cut my toes, tiptoe to the door. Sweet Sue is under my arm, and I take my bloody hand away from my forehead to open the door. But it won’t open. It’s stuck. I’m caught.

Survivors

“A couple of weeks before the tornado I had smashed the end of my left index finger in a swing set and needed stitches. I had shown my neighbor, Ed Smith, my bandaged finger just a couple of days before. When I was blown out of my house and into Mr. Smith I was covered with blood and mud. The bandaged finger was the only way he could recognize me.”

Jim Taylor, 1957 seven-year-old Hickman Mills resident

“I was running toward the front door of the Presbyterian Church, right behind my next-door-neighbor. I saw her make it into the church and a man reached out to grab my hand and pull me in when the wind pushed him away from me and I was blown backwards. I was conscious of being rolled along the ground and then I must have passed out. When I woke up I was by Blue Ridge Boulevard, two hundred yards or so from the church entrance.”

Kathy Tholl McDonald, 1957 seven-year-old Ruskin Heights resident

“My family got in the car and drove away from our house in Grandview, away from the approaching tornado. As we left the house the occluding gust front passed us with very strong winds from the west-southwest. We stopped approximately one mile south and watched the tornado pass to the northeast.

I saw lots of debris in the debris cloud around the base of the funnel. As I recall some of the larger pieces could be seen aloft and some distance away from the funnel.

I knew almost immediately that I wanted to study weather.”

Les Lemon, 1957 ten-year-old Grandview resident, Research Associate Meteorologist and Developer of Doppler Radar

One Song Beyond Hope (a novel)

August 1968

“Hell no, we won’t go. Hell no, we won’t go.”

An angry slash of torn red bunting obstructed Susan’s view out this third-story window of the Blackstone Hotel. A closer look showed her it was attached to a giant poster of Chicago’s mayor reminding them that “Mayor Daley Welcomes You.” It didn’t keep her from hearing the war protesters in the street below. Cautious of remaining tear gas, she opened the window a crack at a time until she was confident this round of gas had drifted out to Lake Michigan. She took two steps to the right, leaned out the window as far as she dared in a miniskirt, and aimed the telephoto lens of her Nikon at the noisy tangle of kids across the street. Maybe she could find Ricky or Kathy. Their anger over the assassinations earlier in the year hadn’t scarred over, and that outrage propelled them right out into the middle of Grant Park. Ruby Slipper had come to Chicago to record an album and make people feel good, but the band’s intentions seemed to be breaking apart, along with everything else.

October 1917

Unbelievably, I am on my way to France. Even now, the Prairie Chief Limited is carrying us from Chicago to New Jersey. In all my twenty-two years I have never been further east that Kansas City. I know only Kemphill and Lawrence, yet Esther, who at eighteen is barely old enough for YMCA work, and I are going halfway around the world because of the war. The only way we know how to live is now part of the past. The only familiar thing we take with us is our music.

Our tranquility ended a little more than a month after war was declared. One morning in May, Papa went to the barn for milking and found the south wall painted yellow. Bright streaks shone in the sunlight over the red paint underneath. Nothing else was touched, and we found no evidence of who had visited us in the night, but it didn’t take us long to figure out who would wish us harm. We later discovered that two other German families in our area awoke that morning to the same vandalism.

June 1968

This was the part Susan liked the most about these gigs. She could really study not just the music but also the way they were all communicating with each other. Maybe it was the photographer in her. It was just so cool to actually see as well as hear their thought process. No matter what had gone down before the gig, who was bummed with who, who owed who money, who had eaten the last donut, when they hit that stage they were completely on the same wavelength. It created one voice. The music was a living, breathing presence of its own born of all of them. Each gig created it differently. Each gig was full of new possibilities. Even with the same tunes, each time was different. It was exciting to hear and watch that process. How could she not want to be a part of that?

They were well into their third tune, an extended version of “Wade In The Water,” a classic gospel funk tune. At least that was the way it started out. Once they played the opening melody, they were off on a wild journey. Sammy laid down the beat, a solid foundation that everyone else built on. He looked so serious with his eyes squinted against the sun, zinc oxide on his nose and cheeks, a headband of braided leather and beads holding his hair back. He was on his own percussion warpath, but everyone else grabbed onto his beat and took off. Ricky played a solo that brought the audience to their feet like he was the Pied Piper. He always said this tune was vermilion. He turned it over to Julius, and, much to Susan’s relief, the two of them grinned at each other as Ricky stood back and just listened to Julius’s solo. Danny and Dave took over from there, playing congas and tambourine before they switched to a horn-and-organ choir in half time playing a very slow version of “Scarborough Fair” against the driving rock beat in the rest of the rhythm section. Then, just when it sounded like they were winding around back to the original tune, Danny’s trombone sang a melodic line from Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade. Picking up on the fugue, Dave carried the melody higher and by some slight of hand back to the melody of “Wade In The Water” again. What a trip.

venmo

venmo